Overview

This page is dedicated to rules and reference information that is most valuable to Game Masters running sessions of Relict. This includes rules that don't come up often or that players don't generally need to know, plus tools, tables, and guides to make GMing easier. Topics covered are:

|

Future topics/tools

Setting Expectations Incorporating Player Characters Establishing (and changing) Goals Creating Conflict Rewarding Players Dangerous Environments |

Curses and Diseases

Random Encounters Wilderness & Foraging (survival rules) Spell Shapes Grid Movement ...& Sizes ...& Range, AoE ...& Squeezing |

Running the World

When to Start An Encounter

Start an encounter--that is, roll for initiative and put player characters into turn order--whenever the sequence of events and moment-to-moment actions of characters will affect the outcome.

Most commonly this is used for combat, but Encounters are a useful tool for GMs for any rapid or high stakes event. Tailing an NPC in a crowd, reacting to a triggered trap, surviving an avalanche, sneaking through a building, and many more. Don't be afraid to roll initiative even for a quick turn if you think it may come in handy! There's no penalty to ending an encounter if it becomes obvious it isn't needed.

Most commonly this is used for combat, but Encounters are a useful tool for GMs for any rapid or high stakes event. Tailing an NPC in a crowd, reacting to a triggered trap, surviving an avalanche, sneaking through a building, and many more. Don't be afraid to roll initiative even for a quick turn if you think it may come in handy! There's no penalty to ending an encounter if it becomes obvious it isn't needed.

Using the Dice

Rolling dice allows us to represent elements of chance in gameplay, in combination with the Core Stats the represent how skilled a creature is. A mighty warrior can certainly swing a sword - but not every blow in pitched combat connects. A cunning trickster may be able to fool or bluff most people they meet - but occasionally, their plans fall flat.

Check rolls determine whether or not an action - be it an attack, spell, ability, social or roleplaying activity, overcoming a physical obstacle, or many other things - succeeds or fails. These are made by rolling 1d12 + [the appropriate Core Stat, as determined by the GM].

Crits. A "natural" 12 on a Check (including Attacks) is considered a Critical Success, and provides several possible beneficial outcomes.

You can read more about Checks, Attacks, and Crits in the Core Rules. Here, we'll be examining the mechanics behind them, and how the GM determines an appropriate Check in more detail.

Elements of a Check.

When to (and not to) Call for A Check

Checks are a vital part of the storytelling and gameplay experience in Relict, but it's not always appropriate to call for one. Asking players to roll Might checks to ensure they can cross a street or climb a staircase, for example, would become tedious, slow, and boring, and do little if anything to move the story along.

How often you call for checks for certain things, how difficult they are on average, and how much leeway you allow for in players discussing different strategies (vs. going with their first kneejerk answer) will come down to how you and your players most enjoy running the game, and may take a few sessions to settle into. However, while there is no hard-and-fast rule for when to/not to call for a check that will apply to every circumstance, we can apply some general rules of thumb.

Call for a Check if:

Check rolls determine whether or not an action - be it an attack, spell, ability, social or roleplaying activity, overcoming a physical obstacle, or many other things - succeeds or fails. These are made by rolling 1d12 + [the appropriate Core Stat, as determined by the GM].

Crits. A "natural" 12 on a Check (including Attacks) is considered a Critical Success, and provides several possible beneficial outcomes.

You can read more about Checks, Attacks, and Crits in the Core Rules. Here, we'll be examining the mechanics behind them, and how the GM determines an appropriate Check in more detail.

Elements of a Check.

- Chance. Rolling the die (usually a d12) represents luck, chance, or circumstances beyond a character's control - for good or ill.

- Skill. The Character's Core Stats provide a "floor" for their abilities, as well as a way to achieve higher results than would be possible for characters less skilled in the areas they excel in.

- For example, a very athletic character with a +7 bonus to Might will never roll lower than an 8 (1d12+7) on a Might Check, and can succeed even on nigh-impossible feats of athleticism when they roll high.

- Strategy. Players choose what course of action they wish to take, but the GM determines the target for success, and what Core Stats apply. GMs should reward players who find ways to leverage their character's/party's strengths to solve problems with lower Check Targets, or by allowing them to use stats the excel at.

- Example 1: a powerful Giant guard is unlikely to be swayed by a warrior's attempt to intimidate it (a Might Check), resulting in a very high Check Target. But if the players surmise that the Giant is easily confused and decide instead to bluff their way past (a Cleverness Check), the GM could set a much lower Check Target.

- Example 2: A complex padlock chains an iron gate closed, barring the party's path forward. A clever character may try to pick the lock (Cleverness), but finds themselves evenly matched. Instead, they could try to determine if the chain or hinges of the gate have weakened over time (a Cleverness Check, or a lower Knowledge Check if the party has a knack for engineering). They could try to brute force a weakness if they find one this way (Might) or construct a lever (Knowledge) to make the force required trivial.

- Example 3: A group of bandits are attempting to shake down a character, but the character cannot get into combat without drawing too much attention from the city guards and ruining their party's heist-in-progress. A proper disguise (Precision) may have avoided this situation, but it wasn't in the cards today. The player could still approach this in many different ways, which would lead the GM to determine what kind of check to call for, and what the consequences of failure or result of success would look like.

- The character may attempt to use Might to intimidate the bandits into going away, but this risks sparking a fight if it fails.

- Instead, the character could try using guile (Cleverness) to trick the bandits into thinking they're someone they're not, or convince them that it's in their mutual best interest that they remain undisturbed.

- They could use slight of hand (Cleverness or Precision) to cause a distraction and Hide (Precision) from the bandits.

- An especially bold strategy would be to use Fortitude, or even a different application of Might, to physically resist showing any reaction to the pushing and shoving of the bandits, convincing them that the character is too powerful for them to tangle with.

- Through dialogue, a player may even be able to maneuver the bandit leader into a contest of Willpower, pitting their force of personality and conviction against the bandit's, hoping to give the impression that a fight here would possibly not end well for the criminals.

When to (and not to) Call for A Check

Checks are a vital part of the storytelling and gameplay experience in Relict, but it's not always appropriate to call for one. Asking players to roll Might checks to ensure they can cross a street or climb a staircase, for example, would become tedious, slow, and boring, and do little if anything to move the story along.

How often you call for checks for certain things, how difficult they are on average, and how much leeway you allow for in players discussing different strategies (vs. going with their first kneejerk answer) will come down to how you and your players most enjoy running the game, and may take a few sessions to settle into. However, while there is no hard-and-fast rule for when to/not to call for a check that will apply to every circumstance, we can apply some general rules of thumb.

Call for a Check if:

- There's a significant risk of failure. Trivial, routine activities shouldn't be cause for a Check, even if there is a very minor risk. If a character regularly rides horses, calmly riding a horse from point A to point B shouldn't require a check. On the flip side, a character with no experience on horseback might be subject to a chance of mishap on their first ride, so a Check could be appropriate.

- Chance of Extra Success. Some activities are low risk, but may be worth a Check if there's a chance that something special could happen on a massive success. Pouring drinks in a tavern would normally not be something to roll for, but if a character is trying to put on a show for the patrons to earn some extra coin, they could roll a Check to see if their performance and/or mixology impresses the crowd.

- The outcome would have no effect. Rolling Checks that don't impact the scene, story, encounter, character, or have any consequence can quickly erode the sense of stakes or investment players have in the game. This doesn't mean that every check needs to have dire consequences - humor and levity are valuable parts of many games! But if the Check doesn't change what happens next in any way, it probably doesn't need to be rolled.

- Success or failure would be bad (for the game, not the characters). There's some nuance to this, but the simple version is: if you don't want the character to fail the check, don't give them a chance to. For example, if it's vital to the campaign that the party enter the city, it may be a bad idea to make them convince the guards to let them in. If the quest can continue once they're turned away, that's one thing, but if their failure to find a way in is going to dismantle everything you planned, perhaps the city gates are just open that day.

- It's for inter-player interactions. Again, there's some nuance here, and above all else this can be easily resolved with out-of-character conversation between players. But in general, don't give one player the ability to make decisions for another via a roll of the dice. If Jack thinks the party should take a boat, but Keith thinks they should rent horses, they should arrive at a decision through roleplay and conversation (in character or otherwise, if need be). It would be inappropriate - and often, supremely fun-killing - to say that Jack can roll a Check to simply persuade Keith's character to do something they explicitly do not want to do, unless both players decide they want to leave it to chance and say as much.

- It's requested. Sometimes players will ask if they can make a Check to accomplish this or that. For example, "can I roll something to see if that NPC is telling the truth?"

- This is usually great; an opportunity to expand on something players are interested in, encourage engagement with the story, enhance immersion in a scene, or have a moment with that character. When possible, it's best practice to allow such requests.

- However, the GM determines if the roll happens, and when. Perhaps the request would run up against one of our Don't guidelines above, or would be incongruent with what's currently happening in the game ("no, you cannot roll to investigate the potted plants while I'm describing the dragon king crashing through the ceiling"). The GM can also delay a Check for a moment ("you can look at the plants after the dragon king is done eating the priest").

- Finally, remember that it's fine to have above-the-table (out of character) talk with your players if you find yourself needing to refuse their requests and they don't understand why. ("The potted plants aren't going to be important in this scene, just give me a second. Now, you all hear the thunderous beat of wings outside...")

Seducing Dragons (And other Salacious Solicitations)

*sighs in GM*

This became an immediate question before we even started playtesting, which I really should have anticipated. But it turned into a pretty great example of two ways a GM could approach social Checks, so we're diving in.

Relict does not have an explicit catch-all "beauty" or "likability" stat. So, if a player wants to flirt, charm, seduce, or tantalize, there are two ways to handle it.

The Simple Answer: it's probably a Cleverness Check. Cleverness covers charm, guile, performance, and being a personable conversationalist; most forms of flirtation can be justified as falling under that general domain.

The Nuanced Answer: Factor in the character's approach, and what the dragon (or NPC) is into. One NPC may be all about bulging muscles, dapper outfits, or sculpted features, while a more scholarly NPC would be underwhelmed by such, but infatuated by a well-read mind who comes with exciting stories to share. Some examples:

This became an immediate question before we even started playtesting, which I really should have anticipated. But it turned into a pretty great example of two ways a GM could approach social Checks, so we're diving in.

Relict does not have an explicit catch-all "beauty" or "likability" stat. So, if a player wants to flirt, charm, seduce, or tantalize, there are two ways to handle it.

The Simple Answer: it's probably a Cleverness Check. Cleverness covers charm, guile, performance, and being a personable conversationalist; most forms of flirtation can be justified as falling under that general domain.

The Nuanced Answer: Factor in the character's approach, and what the dragon (or NPC) is into. One NPC may be all about bulging muscles, dapper outfits, or sculpted features, while a more scholarly NPC would be underwhelmed by such, but infatuated by a well-read mind who comes with exciting stories to share. Some examples:

- Is the character...

- ...trying to dazzle with their physique? A Might Check would be appropriate.

- ...sporting their finest outfit and showing off their sense of style? Precision would apply there.

- ...bantering, bluffing, or trying to impress through wit and humor? We're back to Cleverness.

- ...engaging in passionate discussion on topics of interest to the NPC-I mean-dragon? Could be Cleverness if they're faking it, but definitely Knowledge if the character really has something to say on the subject.

- Is the NPC...

- ...open to attempts, but uninterested in this approach? Increase the Check target.

- ...more interested in a different approach, but still likes the character and is willing to cut them some slack? Set a medium target.

- ...absolutely smitten with the character already? Low target, regardless of approach.

- ...very enticed by this particular approach? Lower the target.

- ...completely unwilling to be approached by this character, or at all? It's okay to set an un-winnable Check or not even call for a roll. This applies here, and also in other "no chance" circumstances. (The best charm Check ever rolled probably couldn't convince a King to give up his throne, for example, even if he really likes the speaker). Try to suggest the impossibility to the player, though.

Flirting with Fellows

When it comes to running flirtation rolls (or other Social Checks) between player characters, the best rule is: don't.

See "When to (and not to) Call for A Check" in the section above.

If players want to explore romantic options between their characters, it should be established out-of-character ahead of time (if not during Session 0), and all parties should be on board with it. As always, I strongly recommend a Session 0 and employing safety tools, especially if playing with unfamiliar people. Regardless, anything in that vein should be explored through roleplay, not gameplay mechanics.

See "When to (and not to) Call for A Check" in the section above.

If players want to explore romantic options between their characters, it should be established out-of-character ahead of time (if not during Session 0), and all parties should be on board with it. As always, I strongly recommend a Session 0 and employing safety tools, especially if playing with unfamiliar people. Regardless, anything in that vein should be explored through roleplay, not gameplay mechanics.

Incrementing the Dice

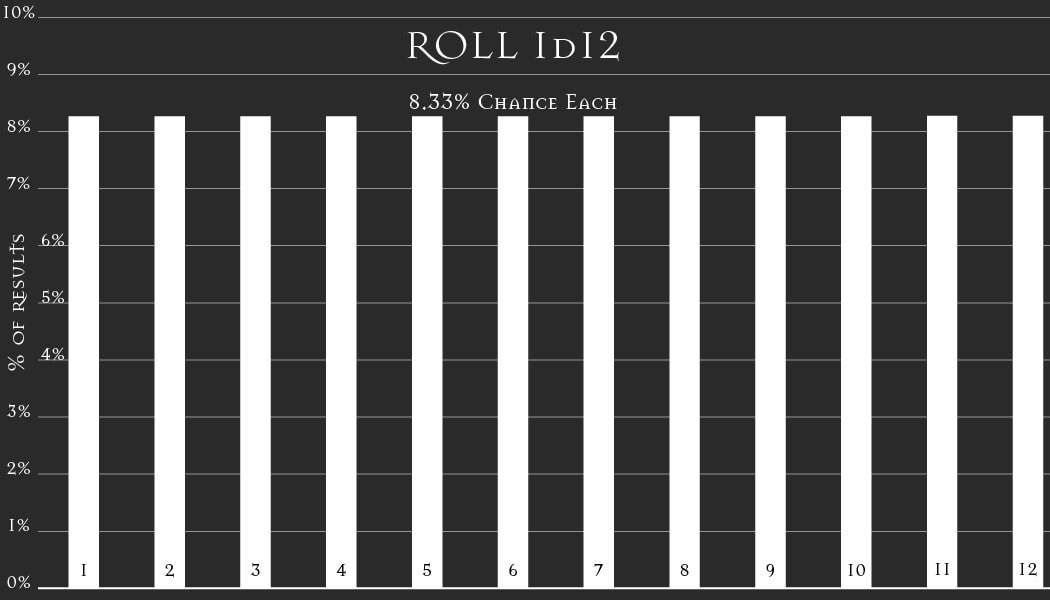

In Relict, the 12-sided dice ("1d12") is the base die that runs most mechanics. If the GM needs a roll, the 12 is where we start.

In some situations, such as a character taking a Longshot, we "increment" the die up or down, meaning we replace the d12 with the next largest or smallest in a standard set.

Note that a "d1" and a "d2" are not included as standard dice in most sets, but you may need to use them for rare situations like extreme long-distance attacks. A d1 would always result in a 1, while a d2 would be a coin flip, resulting in a 1 or 2.

"d3's" exist in some sets, but are rare, and thus are excluded from our definition of a "standard" set.

Remember, if you don't have access to a die size in person, there are many free die-rolling websites available.

In some situations, such as a character taking a Longshot, we "increment" the die up or down, meaning we replace the d12 with the next largest or smallest in a standard set.

Note that a "d1" and a "d2" are not included as standard dice in most sets, but you may need to use them for rare situations like extreme long-distance attacks. A d1 would always result in a 1, while a d2 would be a coin flip, resulting in a 1 or 2.

"d3's" exist in some sets, but are rare, and thus are excluded from our definition of a "standard" set.

Remember, if you don't have access to a die size in person, there are many free die-rolling websites available.

Standard Dice Set - Small to Large

(1) | d2 (coin flip) | d4 | d6 | d8 | d10 | d12 | d20 | d100

Most rolls for most Checks in Relict should be made with 1d12, unless a specific rule or effect says otherwise. See the Check Difficulty Scale below for guidance on setting an appropriate Check Target for the desired difficulty of the task.

However, the GM has the ability to bias the results of a Check by Incrementing the dice used, up or down.

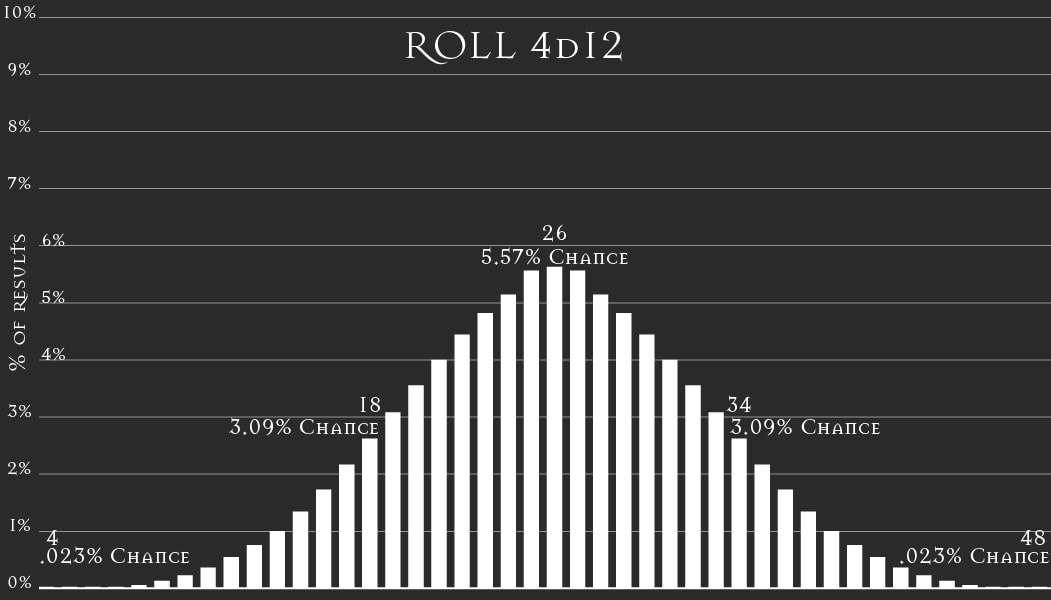

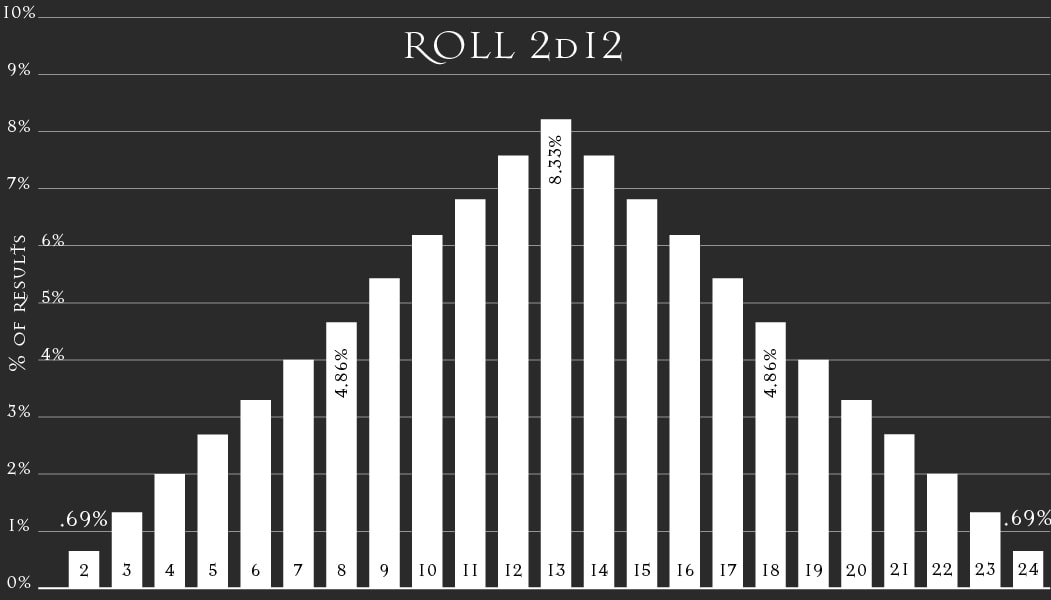

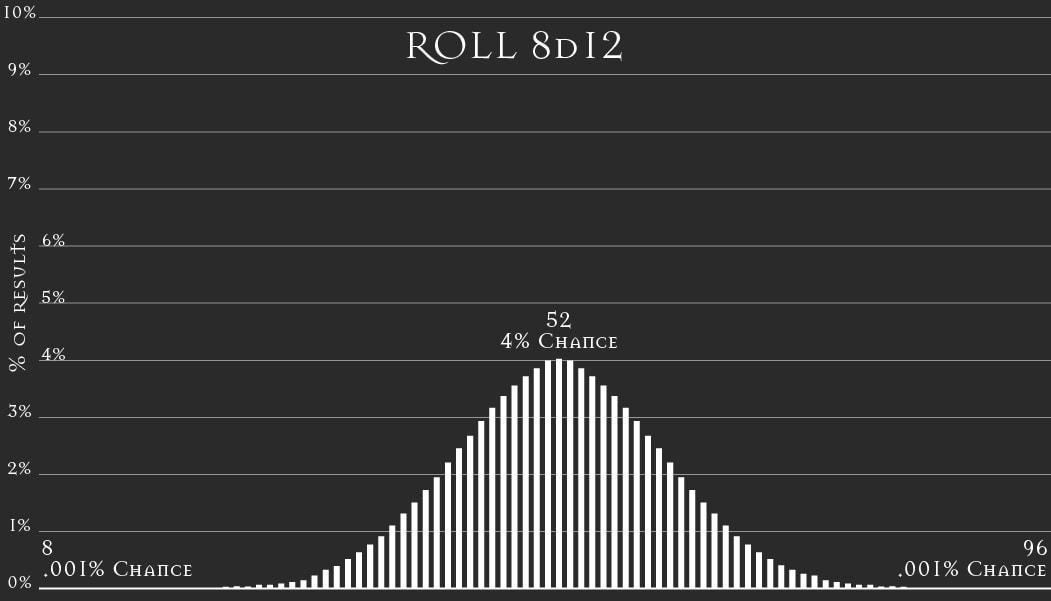

This has two effects, mathematically.

When to Increment.

Other ways to affect the odds.

However, the GM has the ability to bias the results of a Check by Incrementing the dice used, up or down.

This has two effects, mathematically.

- For every 2-face change between die sizes, the average result decreases by 1.

- The average result of a d10 is 1 lower than the average result of a d12.

- The average result of a d6 is 1 higher than the average result of a d4.

- The average result of a d10 is 2 higher than the average result of a d6.

- Incrementing the die changes the maximum possible result.

- Note that a "12 on a d12" is considered a crit--so changing the die removes the chance of critting!

When to Increment.

- When instructed by a specific effect. Some abilities and core mechanics in Relict, like Longshots or Dual-Wielding certain weapons, have incremented rolls built into their descriptions.

- When the maximum outcome should be bounded. Some circumstances may arise where the player can only be partially successful - in such situations, removing the chance for a Crit puts a cap on runaway success that doesn't make sense. For example, a character trying to extinguish a raging forest fire by hand might do as well as is possible, but will not be able to extinguish the entire forest with one action. Not without some major magic, anyway!

Other ways to affect the odds.

- Adjust Targets. The simplest way for the GM to adjust the difficulty for a check is to adjust the target up or down. See the Check Difficulty Scale below this section for guidance, or revisit the Using The Dice section above for more details.

- Roll Twice. If the GM believes that success or failure is particularly likely, but still wants to allow for chance, then they have the option to ask the player to roll a Check twice, taking either the better or worse result (GM's choice).

Quick Reference: Check Difficulty Scale

|

2-5: Trivial

6-9: Easy 10-13: Possible |

14-17: Difficult

18-20: Impossible 21+: Legendary |

Quick Reference - Dice Math!

Quick Reference: Average Results

|

Roll -1d4

1d2-1d4 = -1 1d4-1d4 = 0 1d6-1d4 = 1 1d8-1d4 = 2 1d10-1d4 = 3 1d12-1d4 = 4 1d20-1d4 = 8 1d100-1d4 = 48 |

Roll -1

1d2-1 = 0.5 1d4-1 = 1.5 1d6-1 = 2.5 1d8-1 = 3.5 1d10-1 = 4.5 1d12-1 = 5.5 1d20-1 = 9.5 1d100-1 = 49.5 |

Single Roll

1d2 = 1.5 1d4 = 2.5 1d6 = 3.5 1d8 = 4.5 1d10 = 5.5 1d12 = 6.5 1d20 = 10.5 1d100 = 50.5 |

Roll +1

1d2+1 = 2.5 1d4+1 = 3.5 1d6+1 = 4.5 1d8+1 = 5.5 1d10+1 = 6.5 1d12+1 = 7.5 1d20+1 = 11.5 1d100+1 = 51.5 |

Roll +5

1d2+5 = 6.5 1d4+5 = 7.5 1d6+5 = 8.5 1d8+5 = 9.5 1d10+5 = 10.5 1d12+5 = 11.5 1d20+5 = 15.5 1d100+5 = 54.5 |

Double Roll

2d2 = 3 2d4 = 5 2d6 = 7 2d8 = 9 2d10 =11 2d12 = 13 2d20 = 21 2d100 = 101 |

Quick Reference: Possible Results Range

|

Roll -1d4

1d2-1d4 = -3 to 1 1d4-1d4 = -3 to 3 1d6-1d4 = -3 to 5 1d8-1d4 = -3 to 7 1d10-1d4 = -3 to 9 1d12-1d4 = -3 to 11 1d20-1d4 = -3 to 19 1d100-1d4 = -3 to 97 |

Roll -1

1d2-1 = o to 1 1d4-1 = 0 to 3 1d6-1 = 0 to 5 1d8-1 = 0 to 7 1d10-1 = 0 to 9 1d12-1 = 0 to 11 1d20-1 = 0 to 19 1d100-1 = 0 to 99 |

Single Roll

1d2 = 1 to 2 1d4 = 1 to 4 1d6 = 1 to 6 1d8 = 1 to 8 1d10 = 1 to 10 1d12 = 1 to 12 1d20 = 1 to 20 1d100 = 1 to 100 |

Roll +1

1d2+1 = 2 to 3 1d4+1 = 2 to 5 1d6+1 = 2 to 7 1d8+1 = 2 to 9 1d10+1 = 2 to 11 1d12+1 = 2 to 13 1d20+1 = 2 to 21 1d100+1 = 2 to 101 |

Roll +5

1d2+5 = 6 to 7 1d4+5 = 6 to 9 1d6+5 = 6 to 11 1d8+5 = 6 to 13 1d10+5 = 6 to 15 1d12+5 = 6 to 17 1d20+5 = 6 to 25 1d100+5 = 6 to 105 |

Double Roll

2d2 = 2 to 4 2d4 = 2 to 8 2d6 = 2 to 12 2d8 = 2 to 16 2d10 = 2 to 20 2d12 = 2 to 24 2d20 = 2 to 40 2d100 = 2 to 200 |

Exploration

Light, Darkness, & Senses

Environmental conditions affect how creatures perceive the world, and many spells, abilities, or items interact with these conditions. In Relict, you will come across the following terms:

Blinding Light is an area where vision is impossible for most creatures. Vision related checks (such as looking for tracks, deciphering inscriptions, inspecting an object, etc.) are made with 1d6 instead of 1d12 in a Blinding area. Depending on the severity, the GM may call for other checks to avoid suffering the Blinded Condition or Permanent Blindness Affliction when creatures are exposed to Blinding Light.

Bright Light is an area where most creatures can see normally. Daylight, a well-lit room, or close proximity to a torch or campfire in the dark are all examples of Bright Light.

Dim Light describes areas that are only partially lit - like a moonlit night or a dark room with only feeble candlelight. Creatures without Darkvision can navigate in Dim Light, but vision related checks are made with 1d8.

Darkness is an area with no light. Creatures without Darkvision cannot see in darkness at all, and automatically fail vision related checks.

Blind Actions. Many spells and abilities require the caster to perceive the target in order to use them, meaning they cannot be employed against unseen targets. Spells and abilities that require a roll (such as firing an arrow via the Attack Action) are done with a die two sizes smaller than normal against unseen targets (i.e. an attack that usually uses 1d12 would use 1d8. 1d12->1d10->1d8).

Invisibility. Attacks against Invisible creatures are made with die two sizes smaller than normal, they are considered Hidden until detected, and other creatures have a -1d10 penalty on Search Checks to find them. Unless stated otherwise, invisibility ends automatically when a creature takes or deals damage.

Note: "Blind" is a general descriptor here that assumes most creatures/humanoids are sight-based, but this rule applies when dealing with creatures that primarily use another sense to perceive their surroundings. A permanently blind character that relies on hearing would suffer this penalty in a deafening environment, or a monster that hunts via smell would incur this rule when surrounded by a noxious cloud, for example.

Blinding Light is an area where vision is impossible for most creatures. Vision related checks (such as looking for tracks, deciphering inscriptions, inspecting an object, etc.) are made with 1d6 instead of 1d12 in a Blinding area. Depending on the severity, the GM may call for other checks to avoid suffering the Blinded Condition or Permanent Blindness Affliction when creatures are exposed to Blinding Light.

Bright Light is an area where most creatures can see normally. Daylight, a well-lit room, or close proximity to a torch or campfire in the dark are all examples of Bright Light.

Dim Light describes areas that are only partially lit - like a moonlit night or a dark room with only feeble candlelight. Creatures without Darkvision can navigate in Dim Light, but vision related checks are made with 1d8.

Darkness is an area with no light. Creatures without Darkvision cannot see in darkness at all, and automatically fail vision related checks.

Blind Actions. Many spells and abilities require the caster to perceive the target in order to use them, meaning they cannot be employed against unseen targets. Spells and abilities that require a roll (such as firing an arrow via the Attack Action) are done with a die two sizes smaller than normal against unseen targets (i.e. an attack that usually uses 1d12 would use 1d8. 1d12->1d10->1d8).

Invisibility. Attacks against Invisible creatures are made with die two sizes smaller than normal, they are considered Hidden until detected, and other creatures have a -1d10 penalty on Search Checks to find them. Unless stated otherwise, invisibility ends automatically when a creature takes or deals damage.

Note: "Blind" is a general descriptor here that assumes most creatures/humanoids are sight-based, but this rule applies when dealing with creatures that primarily use another sense to perceive their surroundings. A permanently blind character that relies on hearing would suffer this penalty in a deafening environment, or a monster that hunts via smell would incur this rule when surrounded by a noxious cloud, for example.

Hiding & Stealth

Hiding is an Action creatures can take in or out of an encounter to avoid detection, and requires a Precision check. Hiding always fails if it is attempted in plain view of what a character is trying to hide from - they must achieve some form of cover or concealment. The GM determines what constitutes appropriate concealment for a situation; Dim Light may be enough in a large area far from observers, for example, while moving quietly in a noisy area may be enough to hide from hearing-dependent monsters.

Once a creature has successfully hidden, it can move about undetected by other creatures. This usually means fully avoiding the perception of those creatures (such as remaining out of sight), but can also involve more subtle methods, like blending into a crowd.

Hiding automatically ends when the hidden creature takes an overt action (such as an attack or a shout). The GM may call for additional Hide checks whenever a character performs actions that might break their cover, such as picking a pocket, shoplifting, picking a lock, casting a spell, whispering, etc.

Hiding is normally opposed by the Passive Detection of observers, or contended by a direct roll via the Search Action.

Sometimes, a creature may attempt to Hide, not knowing if they were successful - for example, a player may try to hide from a monster in Dim Light or Darkness, not knowing if that creature has Darkvision.

Attacking From Stealth. When a creatures makes an attack with a weapon or spell against a creature that cannot currently perceive it, they may add an additional +1d6 to the Attack Roll. If it hits, they may roll the damage twice, and apply the higher result. These effects only apply to the first attack made against the target that Turn, hit or miss.

Ambushes happen when one group (players or otherwise) kicks off a combat encounter with another group that hasn't detected them yet. This may involve a stealthy character sneaking ahead of the main group to initiate the encounter, or an entire party that is lying in wait or advancing stealthily. Rules for running an ambush are covered in more detail in the Combat section below.

Once a creature has successfully hidden, it can move about undetected by other creatures. This usually means fully avoiding the perception of those creatures (such as remaining out of sight), but can also involve more subtle methods, like blending into a crowd.

Hiding automatically ends when the hidden creature takes an overt action (such as an attack or a shout). The GM may call for additional Hide checks whenever a character performs actions that might break their cover, such as picking a pocket, shoplifting, picking a lock, casting a spell, whispering, etc.

Hiding is normally opposed by the Passive Detection of observers, or contended by a direct roll via the Search Action.

Sometimes, a creature may attempt to Hide, not knowing if they were successful - for example, a player may try to hide from a monster in Dim Light or Darkness, not knowing if that creature has Darkvision.

Attacking From Stealth. When a creatures makes an attack with a weapon or spell against a creature that cannot currently perceive it, they may add an additional +1d6 to the Attack Roll. If it hits, they may roll the damage twice, and apply the higher result. These effects only apply to the first attack made against the target that Turn, hit or miss.

Ambushes happen when one group (players or otherwise) kicks off a combat encounter with another group that hasn't detected them yet. This may involve a stealthy character sneaking ahead of the main group to initiate the encounter, or an entire party that is lying in wait or advancing stealthily. Rules for running an ambush are covered in more detail in the Combat section below.

Overworld Travel

Often it is not important in a game session to measure exact distances between locations and events during an adventure. Generally, any travel in which nothing of note happens, little is risked, or players have no desire to delve into any specific scenes can be glossed over. Such progressions can be simply summarized: "You travel North on the King's Road for nearly a week, until you arrive at the village of Alta..."

Sometimes, however, it becomes useful to examine long-distance travel in detail. For example, if your party is crewing a pirate ship in the vast archipelago of Oasis, travel on the high seas is part of the adventure! Plotting courses, skirting storms, and dealing with unexpected dangers are part and parcel for such a campaign.

This section breaks down how GMs can approach different travel methods consistently and mechanically, choices a party can make about their travel time, and provides some examples. GMs should feel free to use these as-is, modify them to suit their needs, or use them as a template to build on.

Sometimes, however, it becomes useful to examine long-distance travel in detail. For example, if your party is crewing a pirate ship in the vast archipelago of Oasis, travel on the high seas is part of the adventure! Plotting courses, skirting storms, and dealing with unexpected dangers are part and parcel for such a campaign.

This section breaks down how GMs can approach different travel methods consistently and mechanically, choices a party can make about their travel time, and provides some examples. GMs should feel free to use these as-is, modify them to suit their needs, or use them as a template to build on.

Running Travel Sections

When the players decide to go somewhere that will require Overworld Travel, the GM has two options.

Once the GM has this info, they can determine if the party encounters any complications, run any applicable checks (such as hiding or foraging), and describe the resulting travel to the party.

- If the players are not in control of the travel method (i.e. they join a caravan, board a vessel as passengers, or simply do not have more than one option), the GM can simply determine what the appropriate travel pace and route is, consult the info below for how long the journey should take, and decide whether to include any complications during the trip.

- If the players are determining their own course, the GM can ask them some or all of the following questions:

- How are you travelling? (By foot, by horse, rending a wagon, etc).

- What route are you taking? (The GM may list several options here, or leave it fully in the player's hands).

- Are you travelling at a normal pace? (Other options may include a Hard Pace or Half Speed, see below).

- Are you travelling for a standard amount of time (8 hours) per day, or pushing for longer?

- How are you travelling? (By foot, by horse, rending a wagon, etc).

Once the GM has this info, they can determine if the party encounters any complications, run any applicable checks (such as hiding or foraging), and describe the resulting travel to the party.

Travel Terms

Normal Travel. Without a vehicle (such as a ship), a party can travel 8 hours at a time. An average group can travel at a sustainable pace for 8 hours a day, and still be ready for activity or rest during the remaining hours. A party moving at this pace has time for meals, setting up and taking down a modest camp, taking breaks as needed, and so on.

Extended Travel. If a party needs to travel further in a day, they can press on beyond the normal 8 hour travel time. This may incur the Exhaustion Affliction, as described below the travel method.

Hard Pace. Some travel methods allow for setting a faster per-hour pace, usually with a penalty or risk associated.

Half Speed. Groups travelling by foot or riding may opt to travel at Half Speed, allowing them to Forage or use Stealthy Travel.

Complicating Factors. While travelling through the world, some circumstances may affect a party's pace. Once the party decides on their course (and pace, if applicable), the GM reveals whether they run into a complication. Alternatively, the GM may roll on one of the Travel Complication Tables below.

Extended Travel. If a party needs to travel further in a day, they can press on beyond the normal 8 hour travel time. This may incur the Exhaustion Affliction, as described below the travel method.

Hard Pace. Some travel methods allow for setting a faster per-hour pace, usually with a penalty or risk associated.

Half Speed. Groups travelling by foot or riding may opt to travel at Half Speed, allowing them to Forage or use Stealthy Travel.

- Stealthy Travel. Groups wishing to avoid notice or suspicion while on the move can make a Group Hide Check, depicting how well they concealed themselves during a day's travel. The GM sets the target, and decides how many creatures among the group must succeed in order for it to work. Whether or not the check succeeds, the group must move at half speed for the day in order to make the attempt.

- Forage. Creatures can attempt to find food, water (if no fresh source is readily available), or other resources as they travel. A party can make one Forage attempt per 8 hours while travelling through a region at Half Speed. The GM determines what group or individual targets for the Check are appropriate, based on the conditions.

Complicating Factors. While travelling through the world, some circumstances may affect a party's pace. Once the party decides on their course (and pace, if applicable), the GM reveals whether they run into a complication. Alternatively, the GM may roll on one of the Travel Complication Tables below.

- Minor Complication. These setbacks reduce the party's current pace by 25-50%.

- Bad roads, overburdened party, mild injuries, poor weather or visibility, headwinds or currents, blocked roads or damaged bridges, simple river crossings, rough terrain, and so on.

- Major Complication. These setbacks reduce the party's current pace by 50-75%, and may present other dangers.

- Severe weather, no roads/harsh terrain, major injuries, deep mud, ice, or snow, difficult river crossings, rockslides, poor navigation, and so on.

|

Simple Travel Complication Table (Roll 1d20)

1-5: Major Complication 6-12: Minor Complication 12-18: No complications 19-20: Favorable Conditions, pace increases 10%. |

Detailed Travel Complication Table (Roll 1d20)

|

Note: I'll be providing more environment-specific travel tables as I build out Relict (i.e. "travelling on tundra, travelling in deserts...)

These are just some general ones for when GMs need a random element for now.

These are just some general ones for when GMs need a random element for now.

Travel Methods, Speeds & Distance

Below are average travel times that can be used to track a party's adventure. The base figures assume a sustainable pace with no complicating factors.

Travel by foot (includes all alternative personal speeds, such as Fae flight).

Travel by riding (horseback, carriage, wagon, etc).

Travel by sea - Age of Sail (caravel, galleon, junk, etc).

Travel by sea - Age of Steam (steamship, destroyer, passenger liner).

Travel by rail - Age of Steam (steam locomotive or magical equivalent).

Travel by flying mount (pegasus, griffon, etc).

Travel by lighter-than-air ship (zeppelin, airship, balloon).

Travel by foot (includes all alternative personal speeds, such as Fae flight).

- Normal Pace: 16 miles (25.7km) per 8 hours / 2 miles (3.2km) per hour.

- Hard Pace: 24 miles (38.6km) per 8 hours / 3 miles (4.8km) per hour.

- Extended travel: when the party comes to a stop, all creatures make individual Might or Fortitude Checks (creature's choice). The target of the Check is 10+the number of extra hours (after 8) traveled. Creatures automatically fail this Check if they are travelling at a Hard Pace, or after 24 hours of travel, in addition to any effects suffered from skipping rest. Creatures who fail this check suffer the Exhaustion Affliction.

Travel by riding (horseback, carriage, wagon, etc).

- Normal Pace: 32 miles (51.5km) per 8 hours / 4 miles (6.4km) per hour.

- Hard Pace (horseback only): 40 miles (64km) per hour, limit 2 hours. Horses ridden at this pace must be rested for 24 hours afterward, or will be limited to travel at half normal speed until they are.

- Extended travel: when the party comes to a stop, all creatures make individual Might or Fortitude Checks (creature's choice). The target of the Check is 5+the number of extra hours (after 8) traveled. Creatures automatically fail this Check after 24 hours of travel, in addition to any effects suffered from skipping rest. Creatures who fail this check suffer the Exhaustion Affliction.

Travel by sea - Age of Sail (caravel, galleon, junk, etc).

- Nominal Pace (open water): 120 miles (193km) per 24 hours / 40 miles (64km) per 8 hours / 5 miles (8km) per hour.

- Extended travel: a vessel can maintain its travel pace so long as it has enough crew and rations to rotate shifts. Otherwise the crew must drop anchor to rest, or all crew who work an extended shift make individual Might or Fortitude Checks (creature's choice) at the end of their shift. The target of the Check is 10+the number of extra hours (after 8) worked. Creatures who fail this check suffer the Exhaustion Affliction. Creatures automatically fail this Check after 24 hours of work, in addition to any effects suffered from skipping rest. Non-working passengers are not subjected to this Check.

- Variation: heavier/slower vessels may move as slowly as half this pace, while the fastest sailing ships at sea may move as quickly as 1.5-2x.

Travel by sea - Age of Steam (steamship, destroyer, passenger liner).

- Nominal Pace (open water): 600 miles (965km) per 24 hours / 200 miles (321km) per 8 hours / 25 miles (40km) per hour.

- Extended travel: a vessel can maintain its travel pace so long as it has enough crew and rations to rotate shifts. Otherwise the crew must drop anchor to rest, or all crew who work an extended shift make individual Might or Fortitude Checks (creature's choice) at the end of their shift. The target of the Check is 8+the number of extra hours (after 8) worked. Creatures who fail this check suffer the Exhaustion Affliction. Creatures automatically fail this Check after 24 hours of work, in addition to any effects suffered from skipping rest. Non-working passengers are not subjected to this Check.

- Variation: heavier/slower vessels may move as slowly as half this pace, while the fastest steam ships at sea may move as quickly as 1.5x. Vessels in crowded, shallow, or narrow waterways will often drop to 3-10 mph (4.8-16kph) for safety.

Travel by rail - Age of Steam (steam locomotive or magical equivalent).

- Nominal Pace: 900 miles (1448km) per 24 hours / 300 miles (483km) per 8 hours / 50 miles (80.4km) per hour.

- Refueling: a steam locomotive must take on water and fuel every ~150 miles (~240km), if it does not do so at a station. This process takes an hour, meaning that the maximum time a locomotive can travel during a 24 hour day is 18 hours (3 hours moving, 1 hour refueling). These numbers are reflected in the distances listed above. Passenger locomotives in populated regions will often stop at stations much more frequently than this.

- Extended travel: locomotives can maintain a consistent pace so long as they are able to refuel at the required intervals.

Travel by flying mount (pegasus, griffon, etc).

- Normal Pace: 280 miles (480.6km) per 8 hours / 40 miles (64km) per hour.

- Endurance. Flying mounts must land to take food, water, and rest every 7 hours, or they will be unable to continue. This process takes at least an hour, meaning the maximum per-day travel time for flying mounts is 21 hours (7 hours flying, 1 hour resting). This is reflected in the numbers above.

- Hard Pace: 70 miles (112.6km) per hour, limit 2 hours. Mounts ridden at this pace must be rested for 24 hours afterward, or their endurance is reduced to 3 hours flying/2 hours resting, and they will be limited to travel at half normal speed until they are.

- Extended travel: when the party comes to a stop, all creatures make individual Might or Fortitude Checks (creature's choice). The target of the Check is 5+the number of extra hours (after 8) traveled. Creatures automatically fail this Check after 24 hours of travel, in addition to any effects suffered from skipping rest. Creatures who fail this check suffer the Exhaustion Affliction.

- Variation: some mounts may have specific rules or abilities that affect these details.

Travel by lighter-than-air ship (zeppelin, airship, balloon).

- Nominal Pace: 480-1440 miles (772.5-2,317.5km) per 24 hours / 160-480 miles (257.5-289.6km) per 8 hours / 20-60 miles (32-96km) per hour.

- Endurance: the time that lighter-than-air ships can remain aloft without refueling, recharging, or otherwise landing varies from a week or less for smaller ships, to months or years for larger and more advanced vessels. The greatest hurdle for an airship, however, is weight - which means, among other things, limited rations. Regardless of how long the mechanisms or magic of an airship could keep it aloft, it will have to take on food and water for its crew at regular intervals.

- Extended travel: a vessel can maintain its travel pace so long as it has enough crew and rations to rotate shifts. Otherwise the crew must land to rest, or all crew who work an extended shift make individual Might or Fortitude Checks (creature's choice) at the end of their shift. The target of the Check is 12+the number of extra hours (after 8) worked. Creatures who fail this check suffer the Exhaustion Affliction. Creatures automatically fail this Check after 24 hours of work, in addition to any effects suffered from skipping rest. Non-working passengers are not subjected to this Check.

- Variation: airships are unusual vessels powered by magic, physics, and/or luck, and come in a variety of designs across the worlds. The speeds listed here depict a range of vessel types in generalized conditions, but GMs may want to establish precise values within (or beyond) these ranges for specific vessels. Some official Relict settings will provide specific stats for individual vessels or classes of vessel in that world.

Locks & Traps

When your players encounter a lock or trap, decide on its base Check target ("base target"). Higher targets make the lock or trap more difficult to deal with. This follows the same difficulty scale as all other Checks.

Picking a lock takes a Cleverness Check against its base target.

Destroying a lock requires a Might Check, equal to the lock's base target +10.

Alternatively, locks can be destroyed if a single blow deals more than (its base target x 3) points of damage.

Traps can be divided into two categories:

Dealing With Traps.

1. The first step in dealing with a Trap is Detection, which we covered above as Obvious vs. Hidden Traps.

2. The next step is optional: Deduction. A Cleverness or Knowledge Check against its base target will reveal information about the trap:

Picking a lock takes a Cleverness Check against its base target.

- To pick a lock, a character must have a lockpick set (worth 2SP).

- Failing a lockpicking Check by 5 or more destroys the lockpick set.

Destroying a lock requires a Might Check, equal to the lock's base target +10.

Alternatively, locks can be destroyed if a single blow deals more than (its base target x 3) points of damage.

Traps can be divided into two categories:

- Obvious Traps are clearly visible to all, though there exact mechanism may require more investigation. For example, a tripwire across a hallway is easy enough to spot, but what it does may be a mystery.

- Obvious Traps might include hasty, crude, or improvised defenses, or well-crafted traps that are intended to act as a visible deterrent.

- Hidden Traps require a Precision Check to notice, equal to the Trap's base target. They may be automatically noticed by a high enough Passive Detection, the same as a Hidden creature.

- If a Hidden Trap is present when a character enters an area, but they do not automatically detect it with their Passive Detection, the GM should ask for a Precision Check without explaining what it is for.

- We're seeking to avoid a situation where players feel they must crawl through a dungeon requesting a Check every five feet. This way, players always have a chance to find a trap if there is one, and play can continue.

- If a Hidden Trap is present when a character enters an area, but they do not automatically detect it with their Passive Detection, the GM should ask for a Precision Check without explaining what it is for.

- Damage/Condition Traps. Since player characters automatically heal points of damage when not in combat, traps that deal simple damage while out of initiative are not effective. Instead, these traps are bi-modal: they deal damage if triggered in initiative, or they inflict the Condition associated with that damage when triggered out of initiative.

- Example: a basic Fire Trap might deal something like "1d6 Burning Damage in combat, or 1d4 Ignite Counters out of combat".

- Landscape Altering Traps. When triggered, these traps affect the terrain around them. This may include locking doors, destroying staircases, ladders, or bridges, pitfall traps, or traps that introduce complications to an area like sand, water, gas, darkness, acid, lava, and oil. These traps may trigger secondary damage (like fall damage from a pit or burning damage from ignited oil), but their primary function is to alter the player's path forward, making them deal with the complication or find another route. This can include preventing their escape!

- Affliction Inducing Traps. A particularly dangerous kind of trap, these traps introduce a specific Affliction to their victims. When a creature triggers an Affliction trap, it must make a Check against the Trap's base target, or suffer the indicated Affliction. The stat used for this check is most often Fortitude, but the GM has discretion to call for substitutes as needed.

- Alarm Traps. These traps raise an alert to whomever is monitoring them when triggered. This may be a silent alarm, or an overt one.

Dealing With Traps.

1. The first step in dealing with a Trap is Detection, which we covered above as Obvious vs. Hidden Traps.

2. The next step is optional: Deduction. A Cleverness or Knowledge Check against its base target will reveal information about the trap:

- Scoring within 5 points of the target will reveal what the trap's base target is.

- Meeting or beating the target will reveal what type of trap it is.

- Beating the target by 5 or more will reveal exactly what the trap does, and whether it is connected to any other mechanism.

- A creature may only attempt this Check on a trap once. Repeated attempts reveal nothing new.

- Mark It (BT-8). The creature marks the extents of the trap, including its trigger mechanisms and areas of effect, making it visible for creatures that otherwise wouldn't have detected it.

- This is a Cleverness or Precision Check against the trap's (base target -8).

- Failing this Check has no penalty, but it cannot be attempted more than once per trap. Repeating the Check will trigger the trap.

- Trigger it (BT-5). The creature attempts to trigger the trap safely, either up close or remotely with an attack, spell, or tool.

- This is a Cleverness Check against the trap's (base target -5).

- Failing this Check means that the trap does not trigger, and it increases the trap's base target by +2 for all further Checks.

- Note, the GM has leeway to make this Check an automatic success depending on how the players go about it (triggering a rockslide into a minefield may set off the mines with no Check required--perfectly reasonable).

- Disarm It (BT). A Cleverness Check against the trap's base target will disarm the trap, rendering it inert.

- Failing this Check by less than 2 does not trigger the trap, but it increases the base target by +1.

- Failing this Check by 3 or more triggers the trap.

- Reset It (BT+5). The creature temporarily disables the trap, and can rearm it as an Action.

- This takes a Cleverness Check against the (base target +5).

- Failing this Check by less than 2 does not trigger the trap, but it increases the base target by +1.

- Failing this Check by 3 or more triggers the trap.

Jumping, Swimming, Climbing, Falling

Niche movement methods galore. Always round down to the nearest 5ft. when doing fractions of Speed, to a minimum of 5ft.

Jump (Action, costs Movement and Stamina). Choose:

Swimming.

Climbing.

Falling from dangerous heights. Creatures fall at a rate of 900ft. per Round (150ft. per second). Falling damage is dealt according to the distance fallen, to account for acceleration:

Falling from a moving object. If a creature jumps from an object at high speed, but not significant height (such as jumping from a horse, train, ship, etc.), then for every 5 miles per hour (8kph) it was travelling at, it rolls/skids/slides 20 feet and takes 1d6 Kinetic Damage, and lands Knocked Down. The creature can attempt a Might or Fortitude check (target = speed in miles per hour) to halve the damage and distance moved, and to land on its feet instead.

If a creature is falling from both a dangerous height and at off a moving object, ignore the moving object rules and calculate only the falling from height effects.

Designer's note: The fall damage above is based off heavily-abstracted-for-game-simplicity real-life math, based on how fast you accelerate as you fall and how long it takes to reach terminal velocity (when you’re going as fast as you’re gonna go). GMs: falling 50ft. has an average chance of hitting your players with an Affliction, and a slim chance of instant death. Jumping off buildings without a plan is usually a bad idea. Advise them accordingly. Impact at terminal velocity is unsurvivable without outside interference (something slows you down), magic, a miracle, or all of the above. Some abilities (see Dynamancers) do trigger from falling damage, though, so it’s useful to know what the number is and see if the players can come up with a way to do something with it.

For what it’s worth, Houndsong Games is of the opinion that anything that gets hit for 2,000 Kinetic Damage is un-resurrect-able, but the final call is yours.

Jump (Action, costs Movement and Stamina). Choose:

- (Spend 1/2 your speed and 1+ Stamina) Jump forward up to a distance equal to 1/3rd your Speed. For each extra Stamina spent, add 5ft, up to a max distance of half your speed.

- (Spend 2+ Stamina) Jump vertically. Small creatures can reach an object up to 6ft. above the ground, medium creatures up to 10ft, and large creatures up to 13ft. For each additional 4 Stamina spent, increase the reach by 2ft.

Swimming.

- Non-aquatic creatures, or creatures without a set swimming speed, move at half speed.

- You can hold your breath a number of minutes equal to your Fortitude score, minimum 1. After this time you begin to suffocate, and gain the Incapacitated Affliction in 1 minute.

- Incapacitated creatures that cannot breath underwater die in 1 minute.

- Attack rolls are made with d10's instead of d12's. Ranged weapons have their range reduced by half.

Climbing.

- Creatures with a set Climbing Speed may climb as part of normal movement, and are not subject to the below rules.

- Creatures without a set Climbing Speed move at half speed.

- If a creature goes an entire Round climbing or dangling without a break, it must make a Might Check. The target for the check is the number of Rounds it’s been climbing. This number remains until the creature stops climbing, when it begins to reduce at a rate of -1 per minute.

- If the creature fails its Might Check, it must choose to either let go and fall, or gain one instance of the Exhausted Affliction.

Falling from dangerous heights. Creatures fall at a rate of 900ft. per Round (150ft. per second). Falling damage is dealt according to the distance fallen, to account for acceleration:

- Falling less than 30ft: take 1d4 Kinetic Damage for every 10ft. fallen.

- Falling 31ft. to 1800ft. Take 1d20 Kinetic Damage for every 10ft. fallen.

- Falling more than 1800ft.: Terminal velocity. Take 2,000 Kinetic Damage.

Falling from a moving object. If a creature jumps from an object at high speed, but not significant height (such as jumping from a horse, train, ship, etc.), then for every 5 miles per hour (8kph) it was travelling at, it rolls/skids/slides 20 feet and takes 1d6 Kinetic Damage, and lands Knocked Down. The creature can attempt a Might or Fortitude check (target = speed in miles per hour) to halve the damage and distance moved, and to land on its feet instead.

If a creature is falling from both a dangerous height and at off a moving object, ignore the moving object rules and calculate only the falling from height effects.

Designer's note: The fall damage above is based off heavily-abstracted-for-game-simplicity real-life math, based on how fast you accelerate as you fall and how long it takes to reach terminal velocity (when you’re going as fast as you’re gonna go). GMs: falling 50ft. has an average chance of hitting your players with an Affliction, and a slim chance of instant death. Jumping off buildings without a plan is usually a bad idea. Advise them accordingly. Impact at terminal velocity is unsurvivable without outside interference (something slows you down), magic, a miracle, or all of the above. Some abilities (see Dynamancers) do trigger from falling damage, though, so it’s useful to know what the number is and see if the players can come up with a way to do something with it.

For what it’s worth, Houndsong Games is of the opinion that anything that gets hit for 2,000 Kinetic Damage is un-resurrect-able, but the final call is yours.

Roleplay

Cosmology, Magic, and the Ether

Relict provides a standard makeup of the universe to explain the metaphysical elements of many game universes. It covers the origin of magic and extraplanar entities such as gods and demons, and how they relate to the physical world(s) that your games take place in. GMs are welcome to modify or replace this system if they wish.

The Ether Sea Cosmology (Relict Default).

Within this cosmology, the Ether is a vast body of energy within which all other realms drift. The Ether powers all magic in the material realms. Spellcasters draw its raw energy into their world, shaping it as they do to match their desired effect (assuming all goes well). This can be imagined as opening a spigot, or filling a bucket from this energy-sea, and then choosing what to do with the water. A gardener might use it to water their plants, an engineer may use it to power a mill, and a brewer may use it to make their beverages--but all draw from the same source, even if their results are vastly different. More powerful spellcasters can move more water, direct it more effectively, and conceive of better ways to harness it.

Only three realms are not wholly surrounded by the Ether: The Godsmarch (I), The Citadel (IX), and the Outside (XI). We'll discuss them below.

The Ether Sea Cosmology (Relict Default).

Within this cosmology, the Ether is a vast body of energy within which all other realms drift. The Ether powers all magic in the material realms. Spellcasters draw its raw energy into their world, shaping it as they do to match their desired effect (assuming all goes well). This can be imagined as opening a spigot, or filling a bucket from this energy-sea, and then choosing what to do with the water. A gardener might use it to water their plants, an engineer may use it to power a mill, and a brewer may use it to make their beverages--but all draw from the same source, even if their results are vastly different. More powerful spellcasters can move more water, direct it more effectively, and conceive of better ways to harness it.

Only three realms are not wholly surrounded by the Ether: The Godsmarch (I), The Citadel (IX), and the Outside (XI). We'll discuss them below.

Above, we see how various realms relate to one another. Let's go through them:

I-III: The Heavens.

IV-VI: The Near-Material Realms.

VII-IX: The Hells.

X-XI: The Outside.

I-III: The Heavens.

- I. The Godsmarch. This realm is broken up into numerous pocket dimensions, each the personal domain of a different deity, over which they exercise near absolute power. These dimensions are filled with the gods' closest divine servants, and only the rarest mortal souls are ever permitted within.

- II. The Ardent Reach. A sprawling plane of endless skies, mountains, and rivers, shot through with brilliant stars visible even in the neverending daylight. The Ardent Reach is the home of most lesser and unaligned Celestials.

- III. The Sea of Souls. This is the realm into which unclaimed mortal souls fade after death, and new souls are coalesced from the greater whole at birth. The most willful mortals may maintain their cohesion on passing here, experiencing a timeless bliss until they permit themselves to rejoin the Sea, or are called forth again by other means.

IV-VI: The Near-Material Realms.

- IV. The Minor Planes. A shell of demiplanes, pocket dimensions, and splinter realities surround each material plane. This include transitive and astral planes through which most teleportation occurs, fae and shadow realms that closely mirror the material world they surround, and deathly realms that trap spirits as ghosts or echoes. Contact between these minor planes is frequent, meaning that mortals who find their way into one can wander quickly into another if they are not careful.

- V. The Material Planes. The mortal realms, the "real" world; the place your adventurers are almost always from. Depending on your setting, there may be only a single material world, or it may be one of many. These may take the form of a multiverse of parallel worlds, many worlds within a broader material universe, or whatever else you can dream up.

- VI. The Ether. A vast sea of raw energy within which other realms drift, harnessing the Ether is the chief method to power magic.

VII-IX: The Hells.

- VII. The Desolate Wastes. A vast, lightless plane of biting winds, jagged rocks, and roving predators, this is where souls rejected by the Sea of Souls wind up. Often this results from being marked through foul acts or dealings with fiends in life. Mournful souls within the Wastes are tormented and killed again and again for sport by lesser fiends, or beset by some ravenous undead horrors that find their way here.

- VIII. The Inferno. The home turf of most fiends, the Inferno contains many different areas incompatible with mortal life--from plateaus of frozen wind to lakes of noxious fumes--all separated by a boiling sea of magma, which is the only natural light in the realm. Mortal souls may be dragged here by fiends who can claim them from another plane, or cast down as punishment if they draw the personal ire of a powerful Celestial.

- IX. The Citadel of Damnatation. An endless city of black iron, obsidian, marble, and brass under a dark sun rimmed in pale white fire. The Citadel is the home of the Devils, their lieutenants, servants, and soul-cattle. The Citadel is constantly locked into numerous clandestine and overt conflicts between warring Devils, but some districts are protected to allow interplanar trade in the rarest--and often foulest--goods and services in the cosmos.

X-XI: The Outside.

- X. The Pit. In the heart of the Citadel in an obsidian well miles in diameter. Its walls are constantly patrolled by tithed minions from every Devil in the Citadel, whom never fight with each other here whatever their eons of animosity. The well is bottomless, and no light reflects from its walls more than a mile down, even if a source is lowered in by magic. Constructions erected directly above the pit wither and disintegrate, and even the greatest Devils will not risk flying above it. The Pit is occasionally used as a form of execution for immortals, casting them eternally into oblivion--or so it is hoped. No mortal record exists of anything emerging from the Pit. What is known is that the fiends stand vigil here, and neither they, nor their Celestial enemies, will speak of why.

- XI. The Outside. An incomprehensible realm beyond the edge of everything. All that is known of the Outside is that the greatest powers within the Cosmos dread it. Aberrations will sometimes find their way to the Material Planes from here, often in the wake of a terrible etheric calamity. Some mortals have hinted that dreadful alien intelligences beyond comprehension dwell here, but trying to characterize these and their whims is a terribly taxing endeavor on the mortal psyche.

Places of Power

A Place of Power is a location suffused with otherworldly energies. Below, we’ll describe how they fit within the standard Relict cosmology, but GMs are encouraged to alter or replace this concept if it doesn’t fit their worldbuilding. In general, Places of Power may be conceived of as holy sites, leyline intersections, locations scarred by past magic, miracles, or atrocities, places of significant celestial or stellar alignments, places where the fabric between planes is thin, or whatever else the GM determines for their world.

Places of Power provide a location to focus storytelling elements around. They are required for some types of resurrection in Relict (see the next section for more details), and seeking them out may lead the players to villain’s lairs, healing springs, natural wonders, lost relics, or the domains of dragons, furies, and spirits of the land. Places of Power are rare and, when discovered, often fought over. They make ideal sites for arcane rituals, esoteric experiments, holy sanctums, and more.

Places of Power are not required to run a Relict game. Even if you choose to include them, you need not know where every Place is in your world (if they even exist) to start playing, and they are intended to be mysterious enough that locations the party visited previously could have been a Place of Power without them even knowing.

Places of Power are included here as an option within a storytelling toolkit. They can act as quest hooks, lore tie-ins, home bases, waypoints, and more. They exist in game terms as a mechanism to make a location seem (and act) special, but you do not need to design a network of Places to start playing in your world. They can be introduced later in a campaign, if ever—for example, after a player character's death, when the party starts searching for ways to resurrect their fallen companion.

Defining Places of Power.

In the “default” Relict cosmology, the Ether is a vast ocean of unformed magical energy between planes—which makes Places of Power like tide pools, where an unusual amount of etheric energy gathers in one location.

These pools are initially filled with raw etheric energy that directly fuels whatever forces are most prevalent in the area, and take on the characteristics of those forces in turn. A Place of Power located in the heart of a volcano would greatly enhance the volcano’s temperature and volatility, attracting flame elementals and furies that would grow faster and larger than they otherwise would have. A Place of Power located in the sprawling tomb-catacombs of a lost necropolis would fuel the spontaneous rising of undead, and be a sought-after prize for aspiring necromancers or infernal cultists looking to power their rituals.

Places of Power often form naturally, but may also be created through powerful events, or as a byproduct of the prolonged presence of mythical creatures like demigods, titans, dragons, or greater furies. A god, great outsider, or archdevil setting foot on the mortal plane are the kind of events that would create a Place of Power, as might the razing of a city, completion of a great ritual, or the final triumph of a mighty hero. Places of Power might even spawn creatures with a strong affinity for them, or become breaches into other planes that closely align with the energies swirling there.

Places of Power can vary greatly in size, but are generally demarcated in some way. They may be as small as a single room, or as large as a sea or mountain range—however, the rule of thumb is that the larger the Place, the greater the amount of energy involved in its creation, and therefore the more spectacular the inciting event was. GMs have wide discretion here to make Places fit their lore.

Known vs. Unknown.

The Relict system assumes that Places of Power are rarely studied as a comprehensive phenomenon, though their local effects are often noticed. Those that seek out such things may learn to identify Places through their adventures and studies, but average mortals may pass through a Place of Power from time to time without even knowing.

The longtime inhabitants of an area may know of a Place of Power, but not name it in so many words. Thus, a shrewd explorer can identify a likely Place by seeking out folk tales and local legends. “Cursed” or “lucky” locations, unexplained disappearances or miracles, rarely-seen guardians, predators, or tricksters—all these and more may hint that a Place of Power could be nearby.

Even then, a Place can be subtle, especially a lesser one. Communicate their presence to your players through the feelings they inspire—depending on their nature, a Place might instill those who enter with wonder, dread, peace, passion, contentment, and more.

Influence on your World.

The presence of Places of Power can affect entire regions. A province cursed with many infernal or eldritch Places will struggle with blighted crops, roving monsters, undead, and worse, whereas a region blessed with celestial or nature-influenced Places may see great beauty, bountiful harvests, and general prosperity—so long as its inhabitants take care to safeguard them.

When enough of these energy pools cluster in a region, a natural transfer of energy between them occurs. These are noted by mortals as leylines. These leylines spring from Places of Power, but can result in new Places forming if multiple leylines intersect. If these intersections consist of multiple types of energies—say, a leyline strongly affiliated with lightning and storms intersecting a leyline strongly affiliated with infernal or celestial energies—the results can be chaotic or unpredictable, forming regions of strange hybrid environments or even tearing portals into esoteric pocket realms. These Places are often unstable and short lived, as the leyline network will eventually revert to a less chaotic arrangement—though enterprising mages or opportunistic, powerful monsters may take steps to stabilize and exploit

these phenomena when they can.

Waning Presence.

Places of Power are based on concentrations of energy, and are subject to the forces of entropy over long enough periods. This may be on the order of centuries or more for the greatest Places, or fleeting months for the least of them. No matter what, though, all Places eventually fade.

This process is catalyzed by the presence of mortals in great numbers. Places of Power form through great concentrations of energy, and perpetuate through the attunement and perpetuation of specific forces with those energies. Mortal souls are generally a chaotic, confounding factor in that process. A potent Place can tolerate the presence of a few mortals at a time without issue, but the presence of any great population—or even a few powerful mortals that don’t align with the nature of the Place—can spell its unraveling in significantly less time than it would have taken naturally.

For this reason, Places are rarely found near cities, and creatures that rely (or feed) on Places are wary of permitting mortals to linger. Even the most benign of these entities may be selective about what mortals they allow to come and go freely. The nearest thing to an exception are Places that become sites of worship (benign or otherwise), which can persist for a time even in a populated area thanks to the general alignment of most who visit them. But this is like bailing out a sinking ship—it prolongs the process, but doesn’t prevent it.

Places of Power: Types and Effects.

The structure outlined here is a suggested starting point. GMs are welcome to brew their own version tailored to their world.

Categories:

Affinities. Places of Power adopt and magnify the nature of the forces most prevalent in them. Some examples include:

Places of Power provide a location to focus storytelling elements around. They are required for some types of resurrection in Relict (see the next section for more details), and seeking them out may lead the players to villain’s lairs, healing springs, natural wonders, lost relics, or the domains of dragons, furies, and spirits of the land. Places of Power are rare and, when discovered, often fought over. They make ideal sites for arcane rituals, esoteric experiments, holy sanctums, and more.

Places of Power are not required to run a Relict game. Even if you choose to include them, you need not know where every Place is in your world (if they even exist) to start playing, and they are intended to be mysterious enough that locations the party visited previously could have been a Place of Power without them even knowing.

Places of Power are included here as an option within a storytelling toolkit. They can act as quest hooks, lore tie-ins, home bases, waypoints, and more. They exist in game terms as a mechanism to make a location seem (and act) special, but you do not need to design a network of Places to start playing in your world. They can be introduced later in a campaign, if ever—for example, after a player character's death, when the party starts searching for ways to resurrect their fallen companion.

Defining Places of Power.

In the “default” Relict cosmology, the Ether is a vast ocean of unformed magical energy between planes—which makes Places of Power like tide pools, where an unusual amount of etheric energy gathers in one location.

These pools are initially filled with raw etheric energy that directly fuels whatever forces are most prevalent in the area, and take on the characteristics of those forces in turn. A Place of Power located in the heart of a volcano would greatly enhance the volcano’s temperature and volatility, attracting flame elementals and furies that would grow faster and larger than they otherwise would have. A Place of Power located in the sprawling tomb-catacombs of a lost necropolis would fuel the spontaneous rising of undead, and be a sought-after prize for aspiring necromancers or infernal cultists looking to power their rituals.

Places of Power often form naturally, but may also be created through powerful events, or as a byproduct of the prolonged presence of mythical creatures like demigods, titans, dragons, or greater furies. A god, great outsider, or archdevil setting foot on the mortal plane are the kind of events that would create a Place of Power, as might the razing of a city, completion of a great ritual, or the final triumph of a mighty hero. Places of Power might even spawn creatures with a strong affinity for them, or become breaches into other planes that closely align with the energies swirling there.

Places of Power can vary greatly in size, but are generally demarcated in some way. They may be as small as a single room, or as large as a sea or mountain range—however, the rule of thumb is that the larger the Place, the greater the amount of energy involved in its creation, and therefore the more spectacular the inciting event was. GMs have wide discretion here to make Places fit their lore.

Known vs. Unknown.

The Relict system assumes that Places of Power are rarely studied as a comprehensive phenomenon, though their local effects are often noticed. Those that seek out such things may learn to identify Places through their adventures and studies, but average mortals may pass through a Place of Power from time to time without even knowing.

The longtime inhabitants of an area may know of a Place of Power, but not name it in so many words. Thus, a shrewd explorer can identify a likely Place by seeking out folk tales and local legends. “Cursed” or “lucky” locations, unexplained disappearances or miracles, rarely-seen guardians, predators, or tricksters—all these and more may hint that a Place of Power could be nearby.

Even then, a Place can be subtle, especially a lesser one. Communicate their presence to your players through the feelings they inspire—depending on their nature, a Place might instill those who enter with wonder, dread, peace, passion, contentment, and more.

Influence on your World.

The presence of Places of Power can affect entire regions. A province cursed with many infernal or eldritch Places will struggle with blighted crops, roving monsters, undead, and worse, whereas a region blessed with celestial or nature-influenced Places may see great beauty, bountiful harvests, and general prosperity—so long as its inhabitants take care to safeguard them.

When enough of these energy pools cluster in a region, a natural transfer of energy between them occurs. These are noted by mortals as leylines. These leylines spring from Places of Power, but can result in new Places forming if multiple leylines intersect. If these intersections consist of multiple types of energies—say, a leyline strongly affiliated with lightning and storms intersecting a leyline strongly affiliated with infernal or celestial energies—the results can be chaotic or unpredictable, forming regions of strange hybrid environments or even tearing portals into esoteric pocket realms. These Places are often unstable and short lived, as the leyline network will eventually revert to a less chaotic arrangement—though enterprising mages or opportunistic, powerful monsters may take steps to stabilize and exploit

these phenomena when they can.

Waning Presence.

Places of Power are based on concentrations of energy, and are subject to the forces of entropy over long enough periods. This may be on the order of centuries or more for the greatest Places, or fleeting months for the least of them. No matter what, though, all Places eventually fade.

This process is catalyzed by the presence of mortals in great numbers. Places of Power form through great concentrations of energy, and perpetuate through the attunement and perpetuation of specific forces with those energies. Mortal souls are generally a chaotic, confounding factor in that process. A potent Place can tolerate the presence of a few mortals at a time without issue, but the presence of any great population—or even a few powerful mortals that don’t align with the nature of the Place—can spell its unraveling in significantly less time than it would have taken naturally.

For this reason, Places are rarely found near cities, and creatures that rely (or feed) on Places are wary of permitting mortals to linger. Even the most benign of these entities may be selective about what mortals they allow to come and go freely. The nearest thing to an exception are Places that become sites of worship (benign or otherwise), which can persist for a time even in a populated area thanks to the general alignment of most who visit them. But this is like bailing out a sinking ship—it prolongs the process, but doesn’t prevent it.

Places of Power: Types and Effects.

The structure outlined here is a suggested starting point. GMs are welcome to brew their own version tailored to their world.

Categories: